In 2014, 54% of the world’s population lived in urban areas, compared to 30% in 1950, according to the United Nations (UN) World Urbanization Prospects, 2014 Revision. The report estimates that by 2050, 66% of the world’s population will be urban. Africa and Asia, which are currently more rural than urban, are projected to be 56% and 64% urban, respectively, by 2050.

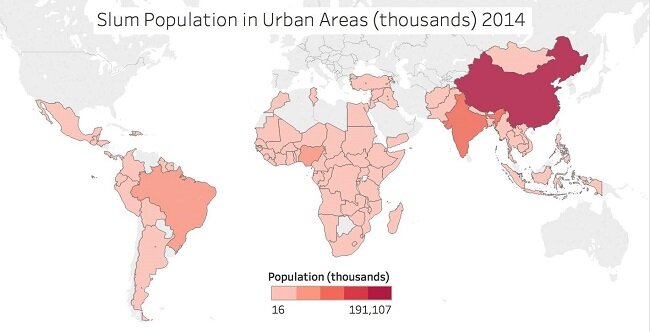

Living in a city does not always mean being more affluent. The UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 11 estimated that 880 million people lived in “slum-like conditions” in 2014. Nearly half the urban slum population – 431 million people – lived in six countries: China, India, Nigeria, Brazil, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Urban slums are defined as having at least one of the following four characteristics:

- Lack of access to improved water supply

- Lack of access to improved sanitation

- Overcrowding (three or more persons per room)

- Dwellings made of non-durable material

These conditions likely do not include gardens for growing vegetables or places to keep animals for fresh milk, eggs, or meat. Instead, the urban poor tend to purchase food from informal markets such as street vendors, according to the 2017 Global Food Policy Report from the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). Yet private sector partners with the Food Fortification Initiative (FFI) said it is very likely that flour sold in informal markets is from industrial mills. Baked goods in these markets are also likely made with flour from industrial mills. As a result, adding vitamins and minerals to flour in industrial mills has the potential to reach the poorest of the poor urban residents.

In Asia’s open markets, wheat flour is usually sold in one to two kilogram bags, said Greg Harvey, CEO of Interflour, one of Asia’s largest wheat milling companies. Harvey is also Chairman of the FFI Executive Management Team (EMT). The small bags may be directly manufactured by flour millers, or the vendor may scoop a small quantity of flour from a 25-kilogram bag to sell to the customer. The small bags usually have no label or branding, but the flour in the larger bag is likely from an industrial mill.

Bread products sold in informal markets may be packaged and branded from an industrial manufacturer or they may be fresh baked goods from a neighborhood bakery. Harvey said small-scale operations typically purchase flour in 25-kilogram bags from distributors who have purchased flour from industrial mills.

That is the pattern in Latin America as well, said Mauro Cerati, Vice President, Global Milling and Global Account Development for Bunge Limited and also a FFI EMT member. As an example, Cerati noted São Paulo, Brazil, a city of 20 million people. The poor population is concentrated in neighborhoods called “favelas.” Residents typically have limited access to transportation, and they frequently shop in informal markets or small, family-run shops near their homes. Cerati said industrial mills provide flour to more than 60,000 bakeries in San Paulo, including small shops called “padarias” which serve both formal grocery stores and informal markets.

Addressing Micronutrient Malnutrition in Urban Settings

Most states in India distribute wheat kernels instead of wheat flour to the low-income population who qualify for the Public Distribution System (PDS). Recipients typically take their wheat allotment to small chakki mills for milling into flour. In these settings, fortification is not practical, sustainable, or cost effective, and the mills lack mechanisms for safety and quality control, said Rita Bhatia, FFI Senior Advisor in India. She noted that urban residents who do not qualify for PDS usually buy flour instead of grain because it saves them the extra time and effort of getting the wheat milled. In a few states, governments are beginning to distribute industrially milled wheat flour instead of wheat kernels. These are the opportunities for fortification to impact millions of people in India.

The urban poor are not the only city dwellers who would benefit from fortification. Urban consumers with higher wages tend to buy prepared and processed foods, and the demand increases when women are in the workforce, according to the IFPRI report. Convenience foods are typically high in salt, fat, oils, and sugar rather than nutrients. As a result, even affluent urban residents may need the nutrients added to staple foods through fortification. Instant noodles are an example of a convenience food which can be made with fortified flour.

One difference between flour and rice sold at informal markets is that vendors typically sell one type of flour but multiple types of rice, said Becky Tsang, Food Fortification Initiative (FFI) Technical Officer for Asia. The vendors are likely dealing with many rice suppliers, some of which might be so small that fortification is not feasible. Yet a recent analysis of rice imports to countries in West Africa indicated that fortification of rice imports had the potential to reach 130 million people – mostly urban residents – in 12 countries.

It is unreasonable to expect government authorities to monitor flour or rice fortification in thousands of informal markets or bakeries throughout sprawling metropolitan areas and far-flung village markets. However the milling industry is centralized in most countries. This means internal monitoring by mill staff and external monitoring at mills by government authorities can ensure that fortification meets the country’s standards before the product is disbursed to bakeries and formal and informal markets.

Already 3.9 billion people globally live in urban areas. The number of people who could benefit from fortification of industrially milled flour and rice will increase as people move to cities and improved infrastructure allows industrially processed foods to spread to rural areas. Since these trends will probably continue, a comprehensive national nutrition program will include both a plan to reach the remaining subsistence farmers and fortification of industrially produced foods to reach the remaining population.

For further reading, see “Addressing Micronutrient Malnutrition in Urban Settings” by Laura Rowe and David Dodson of Project Healthy Children.